90 Days on the Front Line

How UW Medicine led the response to the nation’s first COVID-19 outbreak

“We got one”

It was February 27, and Dr. Lea Starita didn’t have time to think. She just took off running.

Though not the typical way this genome scientist navigated the hallways at work, the news she had to share was of such importance, it more than justified her hurried gait. Time was of the essence — and she knew they’d already lost enough of it.

Arriving at her intended destination, a colleague’s office in the University of Washington Health Sciences building in Seattle, Starita delivered her bombshell: “We got one. What do we do?”

For months, Starita, UW Medicine infectious disease researcher Dr. Helen Chu and their fellow researchers at the Seattle Flu Study — a collaborative effort led by the Brotman Baty Institute in association with UW Medicine, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle Children’s and the Institute for Disease Modeling — had been mailing out and analyzing nasal swabs from people across the Seattle area. They hoped these user-submitted samples would help them track how the seasonal flu and other respiratory infections spread in the community.

Dr. Lea Starita of the Seattle Flu Study helped uncover community spread of COVID-19 in the Seattle area.

But the sample that Starita rushed to tell Chu and her other colleagues about that day in late February wasn’t positive for influenza — it was positive for SARS-CoV-2, the new coronavirus that was sweeping across the world.

More than a month prior, on January 20, Washington became home to the first confirmed COVID-19 case in the United States. Around two dozen more cases were reported in the country following that, but none were in Washington. Public opinion was this was a disease related mostly to travel, and the average person’s risk of infection was likely low.

The Seattle Flu Study’s positive result in a patient who had no recent travel history, however, indicated something more dire: SARS-CoV-2 was in the Seattle area, spreading undetected.

Starita rushed to tell her colleagues about a positive COVID-19 test result in late February.

“The people who present to the hospital are the tip of the iceberg. What about the people who might not feel so good and are staying at home with a cold? It made us wonder what else was out there,” explained Starita, a research assistant professor of genome sciences at the University of Washington School of Medicine and co-director of the Brotman Baty Institute Advanced Technology Lab.

National headlines fixated on the shortage of COVID-19 tests in the United States, but the Seattle Flu Study group had already developed a COVID-19 test by early February, completely separate from their influenza one, after they first learned about the new disease.

The problem was their research lab was not yet certified for clinical testing. Technically, the researchers could test the nasal swab samples they had collected for their flu study and report the results for influenza, but they weren’t allowed to report the results for SARS-CoV-2 tests.

At the end of February, after two weeks of back and forth with state and federal agencies, they decided they couldn’t wait for federal approval any longer. They began testing their nasal swab samples for COVID-19 on a research basis. Only a few hundred samples in, they recorded their first positive.

Back in her colleague’s office, Starita, Chu and the other Seattle Flu Study researchers discussed their next steps.

“We weren’t sure what kind of cascade it was going to trigger and what was going to happen after we found one,” Starita said.

Ultimately, they decided the ethical thing to do was to inform local public health officials. That evening, their positive COVID-19 result hit the news.

Two days later, Washington recorded its first known death due to COVID-19 and Gov. Jay Inslee declared a state of emergency. Within a week, the number of confirmed cases in the state topped 100. Washington would soon become the first epicenter for COVID-19 in the United States.

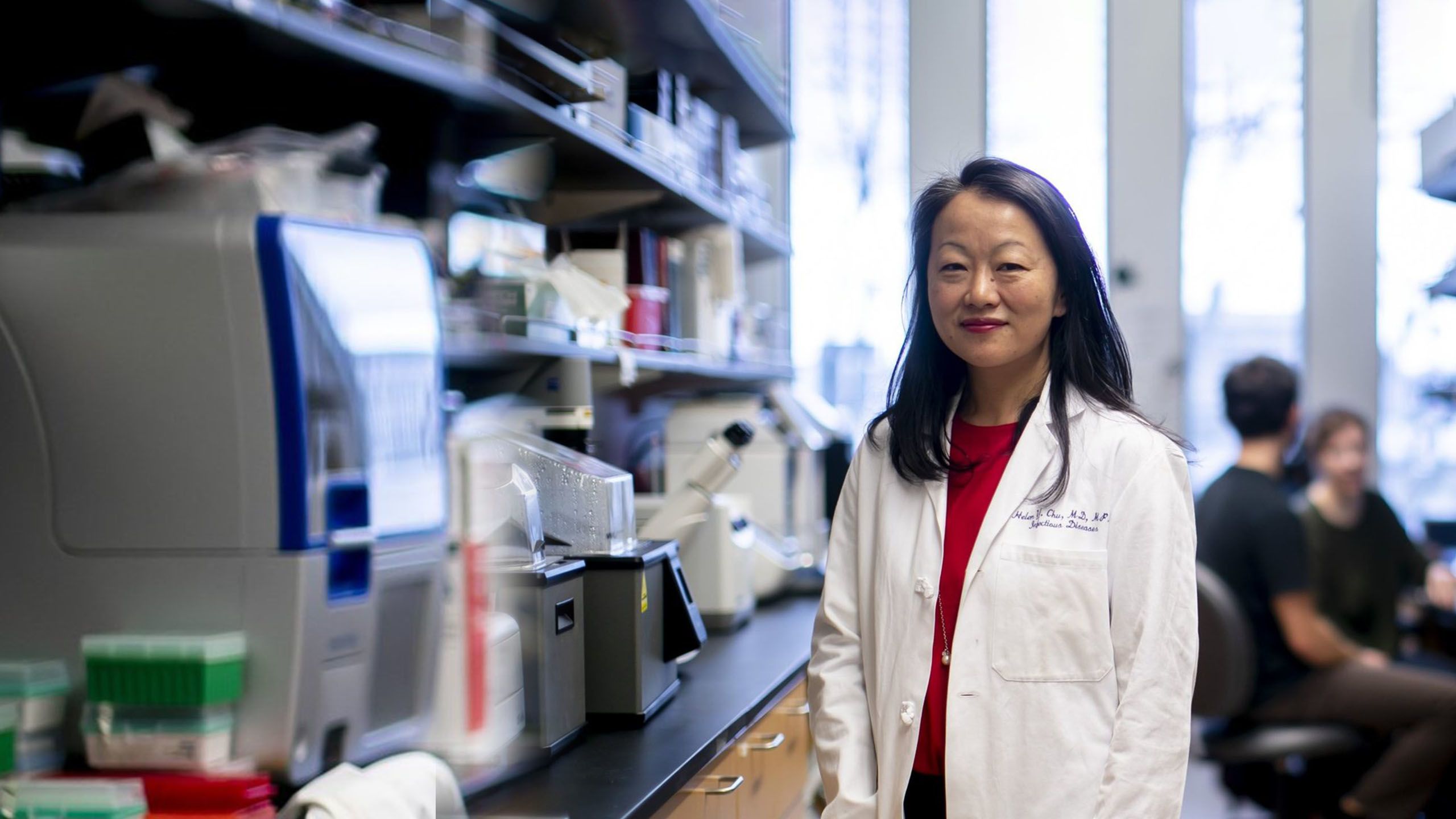

Dr. Helen Chu, one of the lead researchers for the Seattle Flu Study, hoped user-submitted samples would help them track how respiratory infections spread in the community. Photo Courtesy of Erika Schultz for The Seattle Times.

Over the next 90 days, from March through May, experts across UW Medicine would band together in an around-the-clock fight against COVID-19. Their efforts during this time — and also in the months leading up to it — would not only help the state weather the peak of the pandemic but also showcase the strength, resiliency and dedication of the entire UW Medicine community.

JANUARY & FEBRUARY

A mysterious pneumonia of unknown cause

In the early days of January, before COVID-19 even had a name, many people around the world were aglow with the fresh potential of a new year. Medical information networks, though, were lighting up.

Authorities in China were reporting dozens of cases of a mysterious pneumonia of unknown cause in Wuhan, a sprawling city of 11 million.

Across the Pacific Ocean in Seattle, Dr. Alex Greninger read the news with the interest of a self-proclaimed “RNA virus nerd.” He had been part of the team working on the SARS epidemic at the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2004, and these new reports piqued his professional curiosity.

“For people like me who are really interested in RNA viruses, this is what we’re all about,” said Greninger, assistant director of the UW Medicine Virology Lab.

At the time, he didn’t know how the pneumonia was transmitted or if it was even caused by a virus. Still, Greninger decided due diligence was in order. He fired off an email on January 6 telling his colleagues that they should probably make a test just to be prepared. If nothing came of it, he figured they’d at least have something for research purposes.

Shortly after, the world learned the pneumonia was actually caused by a new human coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2. It would be another five weeks before the WHO gave the resulting respiratory illness a name: COVID-19.

Dr. Alex Greninger, assistant director of the UW Medicine Virology Lab, first suggested preparing a test for a mysterious pneumonia in early January. Photo Courtesy of Dan DeLong for The Seattle Times

China reports multiple cases of a mysterious pneumonia in Wuhan.

A Washington man who traveled to Wuhan becomes the first reported case in the United States.

By the end of January, the outbreak spreads to 27 countries and the World Health Organization declares a public health emergency.

Growing concern at home

By the end of January, before most of the community was concerned about a COVID-19 outbreak, UW Medicine infectious disease experts were already in full-on preparation mode.

“When we first heard about cases of COVID-19 developing in China, all of us started thinking about how this is going to impact our community and how we needed to start to prepare,” explained Dr. Seth Cohen, medical director of infection prevention and control at UW Medical Center.

Dr. Santiago Neme, an infectious disease expert and medical director of UW Medical Center – Northwest, also jumped into outbreak planning early on.

“I used to lead the infection control program at UW Medical Center – Northwest and transitioned out of that role in 2017,” Neme said. “But when we heard those early reports of COVID-19 in December, I thought, ‘I’m going to start joining our monthly infection prevention calls again, just in case.’”

Dr. John Lynch, medical director of infection prevention and employee health at Harborview Medical Center, helped manage UW Medicine’s COVID-19 response.

Then after the first COVID-19 case made landfall in late January, Dr. John Lynch, medical director of infection prevention and employee health at Harborview Medical Center, received a call from Public Health — Seattle & King County. Could they activate Harborview’s home assessment team?

The team, a carryover from UW Medicine’s past pandemic preparations for Ebola, got to work. On evenings and weekends, five members traveled to the homes of potential COVID-19 patients, swabbing noses and sending the samples off to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for testing.

“We went to a hotel outside the airport, apartment buildings, people’s houses. Pretty much the entire infection control team here was working extraordinarily long hours,” Lynch recalled.

Dr. Santiago Neme, medical director of UW Medical Center – Northwest, sprang into action, joining the home assessment team to test potential COVID-19 patients. Photo Courtesy of David Ryder.

The Washington Post visited UW Medical Center – Montlake as it prepared for a surge of COVID-19 patients.

Back in the early days of January, he too had read the reports of the mysterious pneumonia, but assumed — or perhaps hoped — the public health authorities in China would be able to contain the illness as they had similar outbreaks in the past.

But now that SARS-CoV-2 had been identified and COVID-19 had already spread to South Korea, Italy and Iran, his concern was only growing.

“We really ramped up our evaluation and awareness of our personal protective equipment setup. We were taking very seriously the work that was needed to develop plans, policies and protocols, and we started meeting daily across UW Medicine to develop all those policies and protocols to prepare for all those people who could show up in our clinics,” Lynch said.

Neme recalled that time period as one of constant activity, tweaking and retweaking policies and then communicating them to hospital staff.

“It was a flurry of updates because the information was constantly evolving,” he said. “And, on top of that, we wanted to make sure the policies were medically sound, approved and implemented throughout the system. Having the same protocols across our system was critical to our safety and effectiveness.”

Dr. Seth Cohen, medical director of infection prevention and control at UW Medical Center, helped coordinate one of the first drive-up testing sites in the country.

By the last weekend in February, when the implications of the Seattle Flu Study’s positive test result had the region reeling, everything seemed to go off the rails at once: A home assessment they performed on a King County woman who returned from Daegu, South Korea, was positive for COVID-19. A patient who passed away at Harborview that week was also positive. So was another patient who had been admitted to UW Medicine’s Valley Medical Center in Renton. And now Life Care Center, a nursing home in Kirkland, was reporting positives among its residents.

“It was a disaster within a disaster,” Lynch recalled.

UW Medicine set up a formal incident command team to help its employees and hospitals navigate what would soon explode into a pandemic.

Lynch worked through Friday evening and Saturday, finally making it back to his home at 1 a.m. on Sunday.

It was only March 1, and things would soon get much worse.

Dr. John Lynch worked with the incident command team to establish protocols for COVID-19 patients.

Dr. John Lynch worked with the incident command team to establish protocols for COVID-19 patients.

UW Medicine’s Valley Medical Center cared for some of the first COVID-19 patients in the region. Photo Courtesy of Valley Medical Center.

“It is no longer business as usual.”

— Tim Dellit, chief medical officer of UW Medicine

MARCH

Testing takes off

Dressed in a button-down shirt and gray zip-up hoodie, Greninger looked at the cluster of microphones and television cameras before him. It was March 4, and he was tired from weeks of nonstop work. But he and the head of the UW Medicine Virology Division, Dr. Keith Jerome, were meeting with members of the media to share a glimmer of good news: they finally had an authorized COVID-19 test.

COVID-19 reagent kit.

COVID-19 reagent kit.

Turns out, Greninger’s early prudence about preparing a test had been spot on. His team had developed one by mid-January, but theirs spent weeks in limbo with the CDC and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) over paperwork, lab certifications and positive control material. Although both the Seattle Flu Study and the Virology Division are associated with UW Medicine, each lab and test needed to go through its own separate set of certifications and approvals.

“I usually never use the phone, but I was making 70 calls a day, waking up early to start on the East Coast, trying to call the CDC, asking for feedback from the FDA,” Greninger recalled.

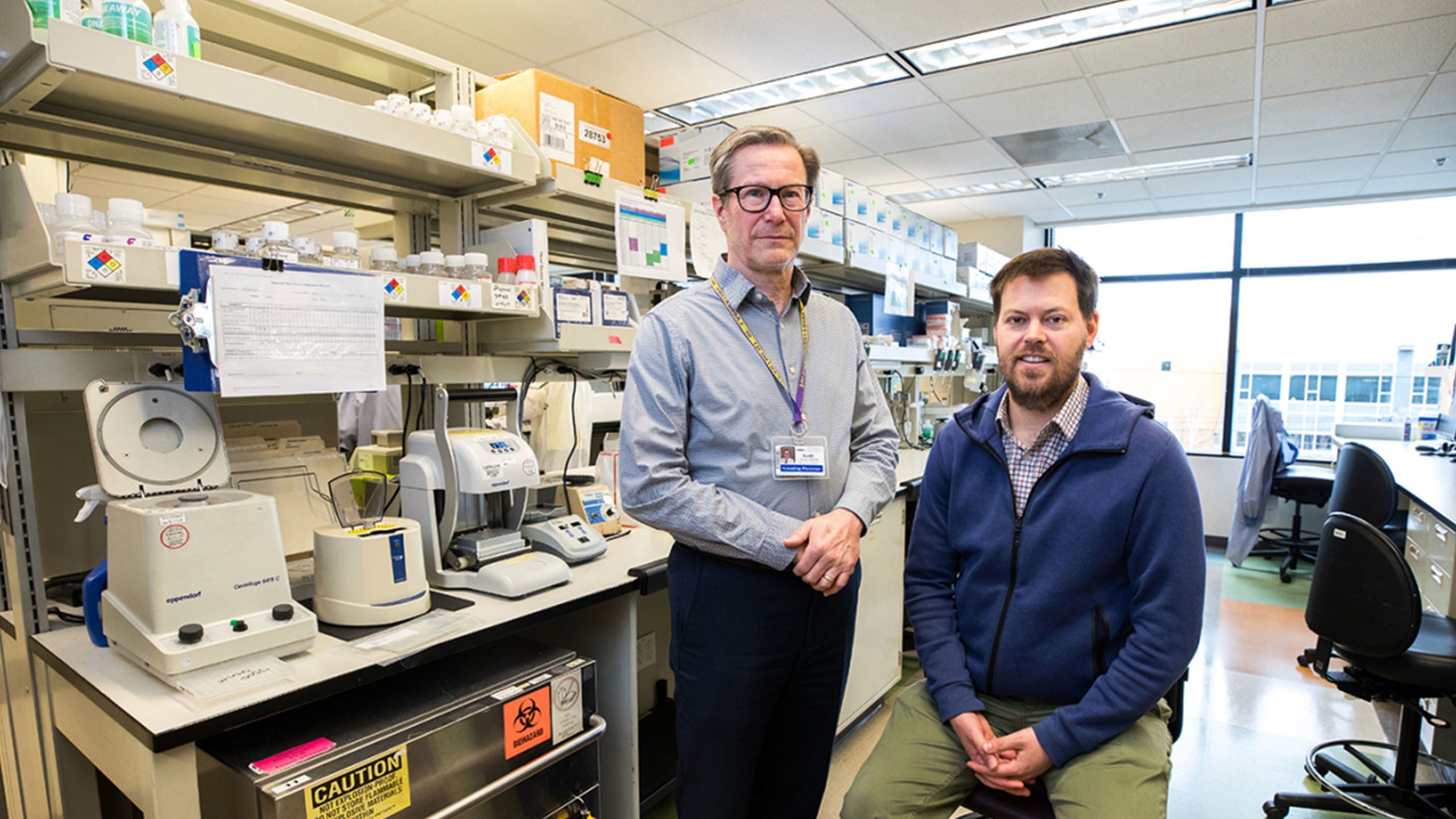

Dr. Keith Jerome (left), head of the UW Medicine Virology Division, and Dr. Alex Greninger, assistant director of the UW Medicine Virology Lab, spearheaded COVID-19 testing efforts. Photo Courtesy of Dan DeLong for The Seattle Times.

With approval finally in hand, their lab rolled out testing to media fanfare. Aside from the Public Health Laboratory, theirs was the only other lab in the state approved to test for the virus.

That first week in March, the lab tested between 500 and 600 samples a day, including nasal swabs collected at UW Medical Center – Northwest, where UW Medicine set up one of the nation’s first drive-up COVID-19 testing sites in the first floor of its parking garage. It only took a few days, however, for Greninger to identify another problem.

“By the second or third day of running tests, I was already thinking about the supply chain. We put out calls to labs across the university for thermal cyclers, tips, labor — just everything,” he said.

With Greninger working with other labs and supply chain partners to get in front of any potential issues, March passed by in a blur of testing.

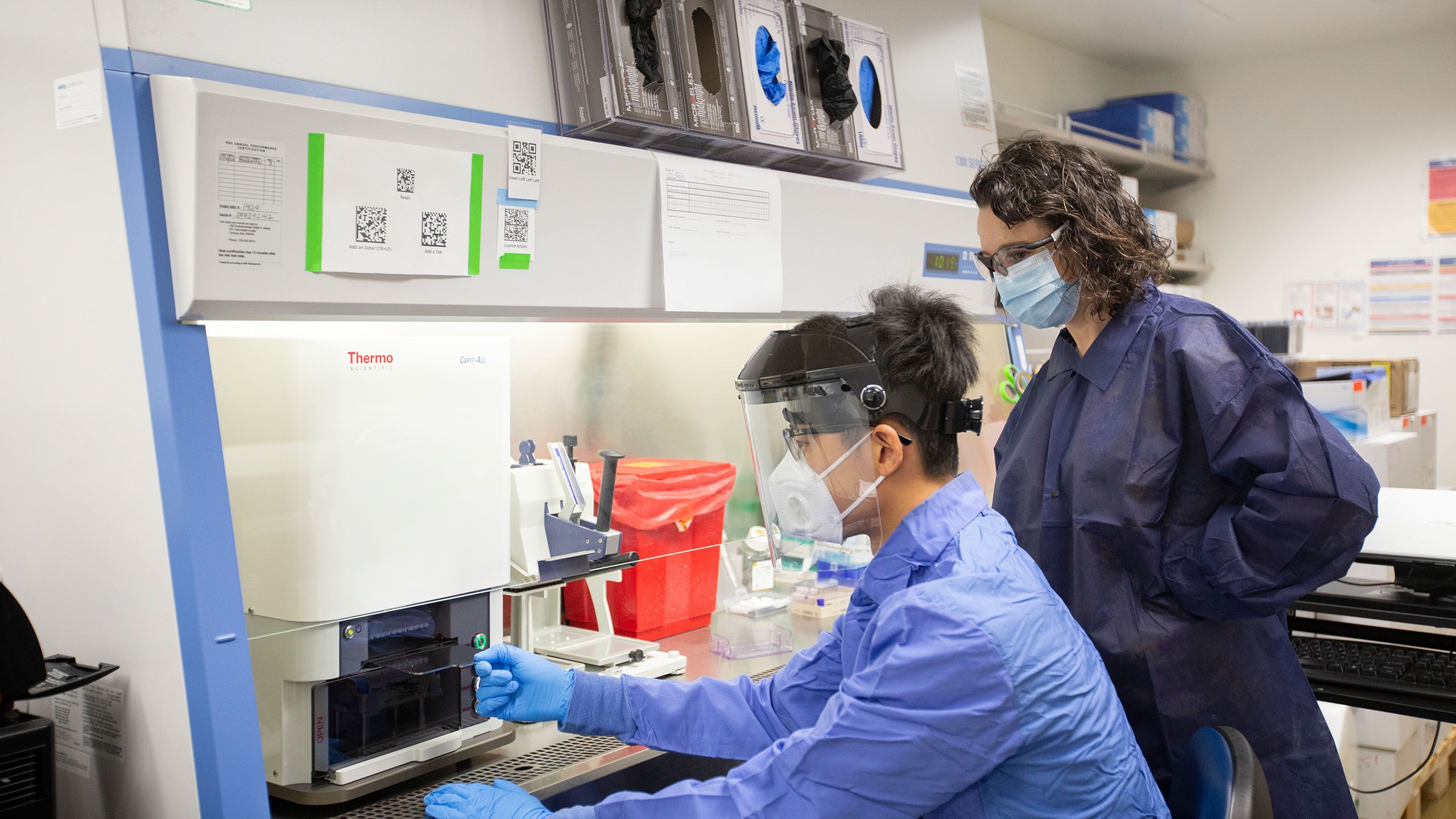

Clinical technicians processed potential coronavirus samples at the UW Medicine Virology Lab. Photo courtesy of Andrew Burton for The New York Times.

Clinical technicians processed potential coronavirus samples at the UW Medicine Virology Lab. Photo courtesy of Andrew Burton for The New York Times.

“We went 24/7. It was pure adrenaline. For months, the number one thing that people were talking about in the United States was laboratory medicine. When does that ever happen?” Greninger said.

It seemed as if everyone in the Department of Laboratory Medicine descended on their lab to help out. They processed specimens, sorted through the FedEx shipments that piled up in the hallways and made calls to the hundreds of patients who tested positive. UW Medicine CEO Paul Ramsey put out a call to lab technicians and researchers to drop their work and volunteer. One of Greninger’s graduate school friends even flew up from San Francisco to chip in.

“In early March, our lab was 70% of the U.S. testing capacity. It wasn’t just UW Medicine patients. We were doing testing for hospitals in Connecticut, California and Oregon,” Greninger recalled.

And they weren’t the only ones trying to tackle testing. By mid-March, Starita and her Seattle Flu Study colleagues were preparing to launch the next iteration of their swab-and-send program, this time focusing on COVID-19 instead of the seasonal flu. It was called the greater Seattle Coronavirus Assessment Network (SCAN).

It took them more than three weeks and 400 pages of paperwork — what Starita described as a feat in itself — to move their work to a lab certified for clinical testing.

On March 23, they formally launched SCAN, in coordination with Public Health — Seattle & King County.

Inside COVID-19 units, front-line staff followed extensive personal protective equipment protocols to stay safe. Photo Courtesy of David Ryder.

Unlike other types of COVID-19 testing, which often required an appointment from a doctor, SCAN was able to provide a testing option for people at their homes, opening up access to those who may not have been able to get a test otherwise. A key goal of the study was to distribute swabs to every part of the county as well as among those who had symptoms and those who had none to ensure a representative sample.

“We only had the infrastructure to send out and receive 400 swab kits a day, and we were trying to make it more equitable by spreading it out on the county. By doing that, we could provide a really important service and help reach underserved communities,” Starita said.

This is where testing needs to be available. Not everyone everywhere, but focused on risk groups and patients in the hospital. At this point in Seattle, if you have respiratory sx +/- fever = probable #COVID2019

— John Lynch (@JohnLynchID) March 14, 2020

Racing to keep up

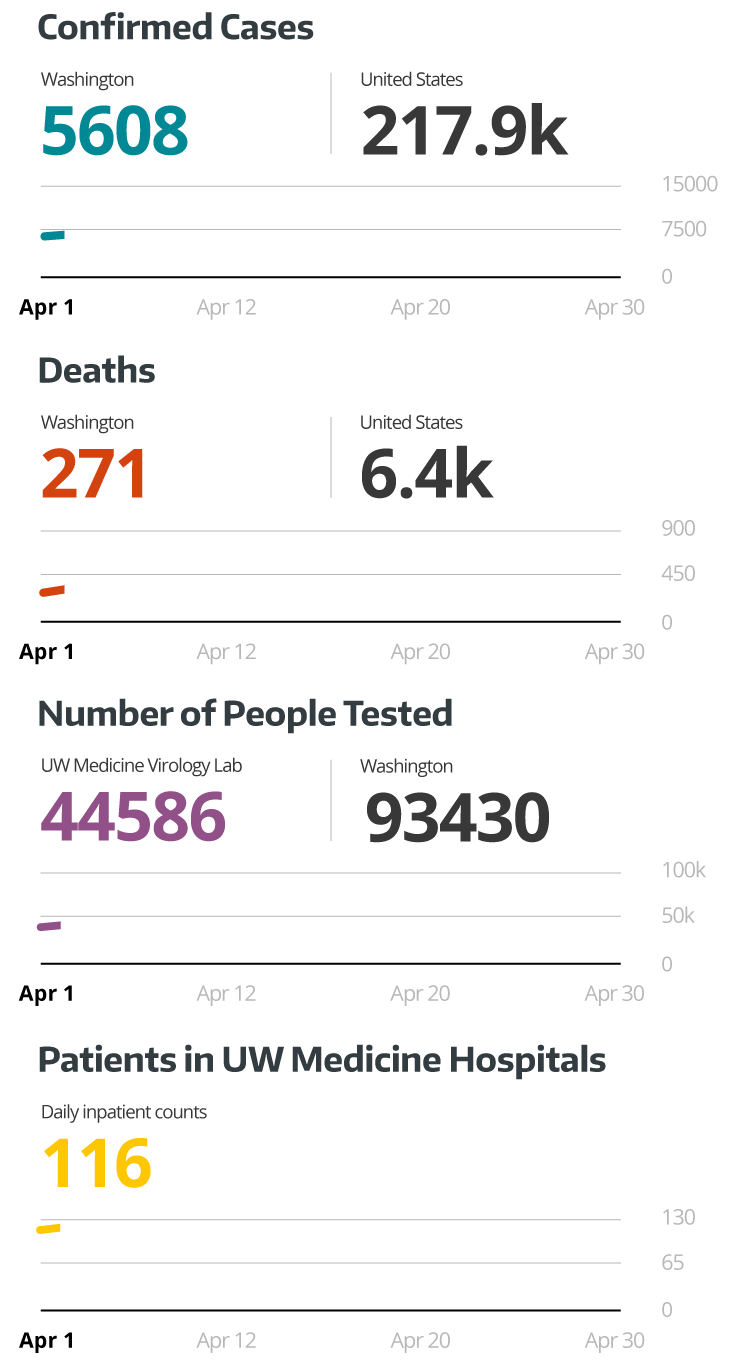

Although testing had cleared its initial hurdles, the situation in area hospitals was growing grim. By late March, Washington’s confirmed COVID-19 cases topped 2,000, and UW Medicine had admitted more than 40 patients to its acute care and intensive care units.

UW Medical Center – Northwest, in particular, was heavily impacted early on in the pandemic as patients from Life Care Center and other assisted-living facilities were admitted with COVID-19.

UW Medicine nurses provided care to critically ill patients during the height of the pandemic. Photo Courtesy of David Ryder.

To accommodate the influx, the hospital campus converted three of its floors into COVID-19 units. Hospital staff were redeployed from other areas like surgery to help patient care teams with the important task of safely putting on and taking off personal protective equipment (PPE). And palliative care specialists huddled together with families in the emergency department to have difficult but necessary conversations about end-of-life care for their loved ones.

Meanwhile, supplies of face masks and eye shields — equipment essential for keeping front-line workers safe — were running low everywhere.

Members of incident command collaborated with UW Medicine’s supply chain team to quickly establish new strategies for obtaining, conserving, tracking and distributing PPE.

“We wanted to not only make sure we had enough PPE but also enough ventilators and beds and all those things that make a hospital work,” Neme said. “As a team, we looked into the possibility of reprocessing equipment and making sure everyone understood our PPE guidelines and the rationale behind them.”

Across the organization, employees jumped in to help. Pharmacists at UW Medical Center began whipping up batches of hand sanitizer to supplement the hospitals’ supply, while researchers used 3D printers to make face shield visors for front-line workers.

At Harborview, Lynch and his infection control team pulled all-nighters to try and keep up. Each evening, one would take a turn sleeping on a camping cot in the hospital office so someone would be available at the hospital if needed. When it wasn’t their turn for an overnight shift, other team members would still be working until 1 a.m. each day — only to be back at it six hours later.

The scene inside the hospital was equally surreal and strange. Some units were eerily empty, with elective surgeries delayed and in-person appointments transitioned to virtual visits. Meanwhile, Harborview’s COVID-19 floors buzzed with near-constant activity.

In the hallways, equipment-laden crash carts lined the walls. Medical staff pulled on gloves, donned protective gowns and slipped on powered air purifying respirator (PAPR) hoods to prepare to enter a patient’s room. Within the negative-pressure rooms, critically ill patients lay still, hooked up to a dizzying array of tubes and wires.

Nurses and doctors rotated in and out, providing care to patients around the clock. Some patients would finally turn a corner and improve. Others would take a turn for the worse, requiring them to be hooked up to ventilators to help them breathe. And for a heartbreaking number, their conditions would deteriorate so much a nurse would have to video call their loved ones so they could say a final goodbye.

“It was a scary time for everyone because we did not know much about this new illness, but our staff pulled together and helped redesign our unit. There was almost a Zen-like calmness in the intensive care unit as we faced our common enemy. We emerged from this ordeal stronger, more tightly knit and smarter,” said Dr. Richard Wall, medical director of the critical care unit at UW Medicine’s Valley Medical Center. Photo Courtesy of Valley Medical Center.

“It was a scary time for everyone because we did not know much about this new illness, but our staff pulled together and helped redesign our unit. There was almost a Zen-like calmness in the intensive care unit as we faced our common enemy. We emerged from this ordeal stronger, more tightly knit and smarter,” said Dr. Richard Wall, medical director of the critical care unit at UW Medicine’s Valley Medical Center. Photo Courtesy of Valley Medical Center.

“It was brutal and extremely hard. We saw more infections each day, and the proportions of positive test results were also more than they were previous weeks. When I looked at those general trends, I saw signs that the surge was still ahead of us,” Lynch said.

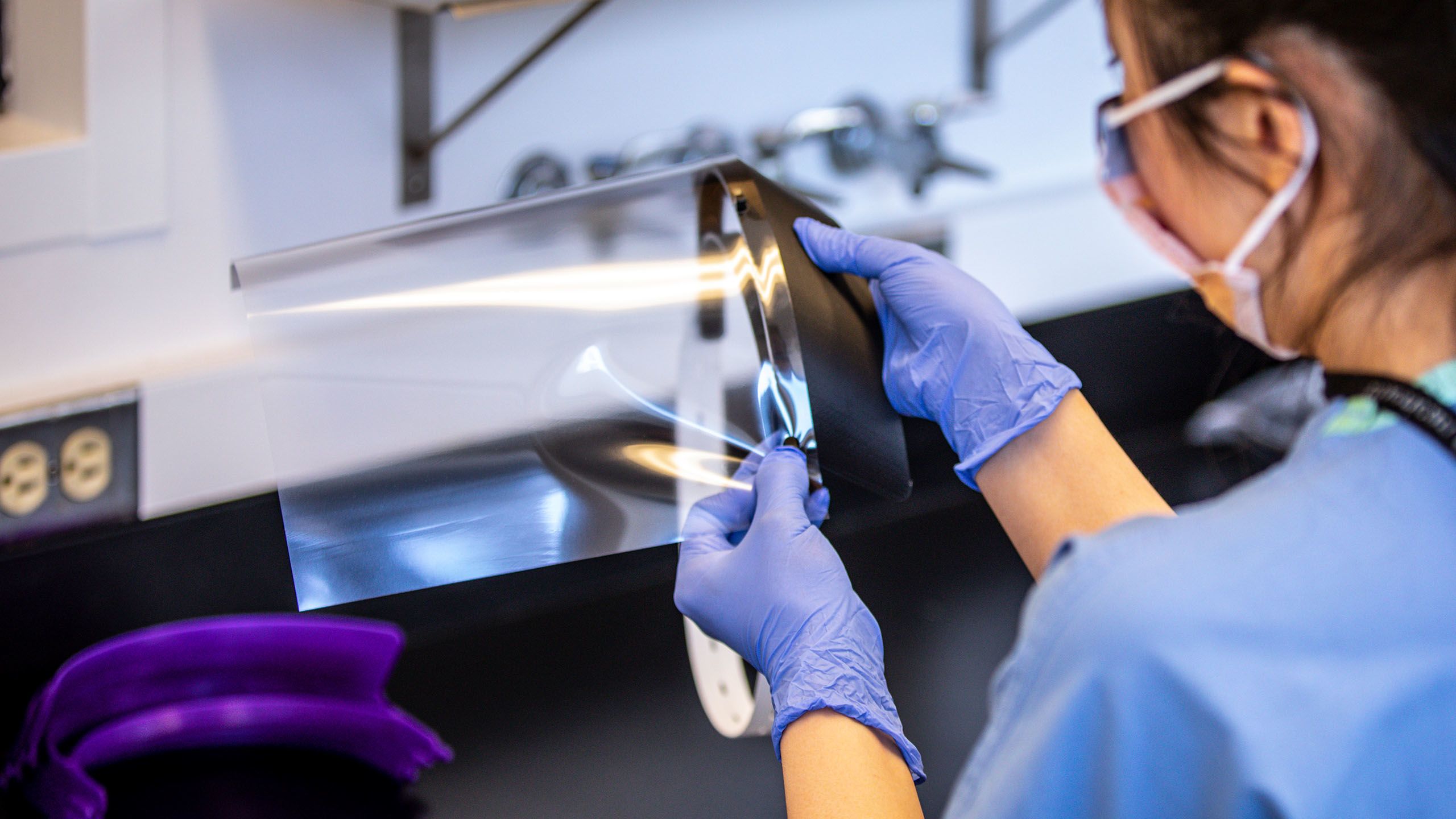

Across UW Medicine, employees found creative ways to obtain more personal protective equipment, including making face shields.

While all of UW Medicine was on the front line, our nurses were pivotal in the care and treatment of our patients. Take an inside look at our nurses’ work amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

While all of UW Medicine was on the front line, our nurses were pivotal in the care and treatment of our patients. Take an inside look at our nurses’ work amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

Predicting the pandemic

When would that surge hit? How large would the peak get? And, most importantly, would hospitals have enough space, staff and resources to respond?

Dr. Christopher Murray, director of the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) at UW Medicine, was thinking about all of this and then some.

Once an executive director at WHO, Murray had plenty of experience with outbreaks like this one. He and others at IHME watched the COVID-19 outbreak unfold from the beginning, knowing there was a chance it could be contained but also a chance it could explode.

“We didn’t leap into the fray at first, but then the tipping point came when we saw the outbreak in Italy, then Washington and at the Life Care Center in Kirkland,” Murray recalled.

Dr. Christopher Murray, director of the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at UW Medicine, pulled together a team to model how COVID-19 would affect hospital systems. Photo Courtesy of IHME.

That’s when UW Medicine officials made a request: Could IHME model what would happen to their hospital system during the COVID-19 pandemic?

It would require IHME to invent a completely new type of model, so Murray put out a call for volunteers. Of the 500 people who work at the institute, nearly 100 joined the COVID-19 team.

“We rapidly pivoted from our usual work to doing a lot more work on this challenge because it was so pressing,” Murray said.

It would normally take them up to a year to build a statistical model that could predict the growth, magnitude and duration of an infection. But in this case, it took the IHME team 10 days to launch their model for UW Medicine hospitals and another 10 days to expand it to the rest of the United States.

It can take IHME around a year to build a statistical model for an infection, but it took them only 10 days to launch their model for COVID-19. Photo Courtesy of IHME.

Their model confirmed what Lynch had predicted. The worst was still yet to come.

APRIL

Surviving the surge

By early April, signs of UW Medicine’s surge preparations were everywhere.

At hospitals, mask-clad staff members bustled about, many physically and emotionally exhausted after weeks of running on fumes. Large white tents were erected outside emergency departments to serve as temporary triage stations for the anticipated swell of patients with respiratory symptoms. And, inside, architectural plans were drafted to figure out how dedicated COVID-19 floors could be reworked to accommodate any overflow.

“Our infection prevention specialists across UW Medicine were constantly fielding questions from staff and doing a ton of work,” Cohen said. “There was a period where all of us were going 24/7. It was a very dark time.”

Lynch concurred.

“I’ve dealt with exposures and outbreaks, like measles, tuberculosis and Ebola — all kinds of stuff. Like many others, I’ve taken care of people with influenza and other infections who get very sick and die. I’ve seen a lot over the years, but this was by far the worst,” he recalled.

Staff at Harborview Medical Center prepared for incoming COVID-19 patients.

Despite it all, Lynch didn’t lose hope, even as UW Medicine’s number of admitted COVID-19 patients swelled.

“I’m pathologically optimistic. I felt like we had the capability to take care of patients and to respond pretty effectively. When we started physical distancing at the city and state level, a monumental public health intervention that was impossible to imagine before this, I put a lot of faith in that,” Lynch said.

Making a new model

While front-line workers continued to care for an overwhelming number of COVID-19 patients, the team at IHME was fine-tuning their model to help predict just when the surge would be in sight.

“It was a constant race to improve the model and a constant flurry of work,” Murray said.

As updated numbers rolled in, they soon realized the peak — originally anticipated to hit in mid-April — had started to plateau after April 12. It was a pleasant surprise, but one that made Murray and his team reexamine their work.

Dr. Christopher Murray, director of the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at UW Medicine, discussed their COVID-19 model with CNN’s Anderson Cooper.

“We based our first model on the Wuhan experience, but we realized that our experience here was more like what happened in Italy and Spain. Instead of the curve going up steeply and down steeply as it did in Wuhan, the curve went up steeply and had a slow decline,” Murray explained.

In the middle of April, the IHME team started to intensely rework their model. They finalized it and, on May 10, shared their new predictions: If physical distancing measures continued to be relaxed, as they were already doing in some states, more than 135,000 people in the United States would die from COVID-19 by early August.

Sprinting in the middle of a marathon

By April, the Virology Lab had made its way through 75,000 samples. UW Medicine had expanded its testing sites to include drive-up testing for patients and employees as well as mobile vans that traveled to underserved communities.

At that point, the Virology Lab’s core team of 30 and some additional 40 volunteers were running 7,000 tests a day, with a turnaround time of six hours. Somewhere in the middle of all that testing, they moved their lab to a new floor and increased their biosafety cabinet space sevenfold.

COVID-19 samples awaited processing at the UW Medicine Virology Lab.

COVID-19 samples awaited processing at the UW Medicine Virology Lab.

Then came antibody testing.

These tests, also called serology tests, check a patient’s blood for signs of a past infection. By understanding who had been infected with COVID-19, perhaps unknowingly, public health experts hoped to better understand just how far the pandemic had spread.

“Our immunology colleagues brought us four or five different serology tests, and we were able to pull serum samples from people who were positive and figured out which tests did well. The test from Abbott Laboratories did better than all the rest. It was more sensitive, had higher throughput and was cheaper,” Greninger recalled.

On April 17, the Virology Lab announced that, in addition to processing thousands of COVID-19 samples each day, they’d also now be doing the bloodwork for antibody tests. The work was necessary but no less daunting.

“It felt like sprinting at mile 10 of a marathon,” Greninger explained.

MAY

Results and reopening

On May 1, Gov. Inslee extended Washington’s stay-at-home order by another month. But with the curve sufficiently flattened, quiet grumblings about reopening the state only grew louder.

WATCH: I’m giving an update on our COVID-19 response at 2:30 PM. I’ll be joined by @WADeptHealth Secretary John Wiesman and Vice Admiral Dr. Raquel Bono.

— Governor Jay Inslee (@GovInslee) May 1, 2020

Tune in here: https://t.co/pWx42pfhp7 pic.twitter.com/eh4by8nlDS

Other states were relaxing restrictions. When would Washington follow suit?

To Starita and her SCAN colleagues, their results showed it was simply too early. By early May, they had processed more than 12,000 samples from people all across King County.

What they found was that in the first half of May, the community still had between 3,000 and 10,000 active COVID-19 infections. Reopening prematurely could have disastrous consequences.

“At SCAN, we’re actively working to figure out where the disease is and how to combat it,” Starita said.

Meanwhile, Murray and the IHME team tweaked their mortality model again. With more restrictions being relaxed across the country, they now predicted that 147,000 Americans — up 10,000 from their previous projection — would die from COVID-19 by early August.

“For us on the modeling side, we have to guess how governments and individuals will respond. From there, we do various scenarios that have nothing to do with the virus but rather are about predicting the behavior of governments and individuals,” Murray explained.

Although the numbers seemed to be trending downward in Washington, the state’s continued success would depend entirely on how people responded once businesses reopened.

Lisa Brandenburg, president of UW Medicine hospitals and clinics, offered rationale for a variety of measures to keep patients and staff safe, which included proactive COVID-19 testing for all patients before surgical procedures and mandatory screening of all UW Medicine staff.

Lisa Brandenburg, president of UW Medicine hospitals and clinics, offered rationale for a variety of measures to keep patients and staff safe, which included proactive COVID-19 testing for all patients before surgical procedures and mandatory screening of all UW Medicine staff.

A cautious exhale

As for infectious disease specialists Lynch, Cohen and Neme, they spent the end of May mulling over what they just experienced and what was yet to come.

In the early days of the outbreak, they and others on incident command focused on establishing new COVID-19 protocols and partnering with the supply chain team to ensure front-line workers had sufficient amounts of PPE to safely do their jobs.

Researchers across UW Medicine and the University of Washington contributed to COVID-19 response efforts by making masks and face shields.

Researchers across UW Medicine and the University of Washington contributed to COVID-19 response efforts by making masks and face shields.

By the end of May, UW Medicine had gone through tens of millions of pieces of PPE — everything from masks and gowns to gloves and face shields — and developed more than 70 policies and protocols in response to the outbreak. Having been at ground zero for the outbreak in the U.S., they saw it as their responsibility to not only document what worked well for UW Medicine but to also share this information with other hospitals across the country.

“Those initial three months were pretty much work all the time,” Neme said. “Our leaders were discussing difficult topics and then coming up with a consensus and a response that made sense — policies and protocols that are evidence based and that people can feel confident around.”

Assessing all that had happened, Lynch and Cohen knew that the effects of the pandemic would continue to ripple for months to come — not just for the community but for front-line workers as well.

“The UW Medicine community really supported each other,” Cohen said. “A big part of surviving that April surge was creating a culture of gratitude and keeping staff morale up. Our team did an incredible job of staffing hot zones, even though none of them anticipated being part of a response to a novel pandemic.”

“We’ve had incredible support. People are stopping us to say thank you, dropping off food, you name it. But we are going to have this with us for a long time. At some point, you just do too many days of doing too much and you can’t keep up,” Lynch added.

He could only herald the importance of continued testing and public health efforts like masking and physical distancing to help curb COVID-19.

“The potential for another surge is very real if we don’t take precautions. Sure, it didn’t turn into the movie ‘Contagion’ yet, but that’s because everything we did worked. Public health is really successful when terrible things don’t happen,” Lynch said.

Toward the end of May, as the number of COVID-19 patients and positive tests continued to go down each day, it would be impossible for anyone to predict the resurgence that would soon swell in the coming summer months.

UW Medicine and University of Washington groups used more than 70 3D printers to create face shield visors for front-line workers.

But in that short window of success, the infectious disease experts finally allowed themselves a much-deserved sigh of relief. And then they got back to work.

Healthcare workers at Harborview Medical Center kept their scrub bottoms clean by wearing colorful patterned socks. Photo Courtesy of Karen Ducey for Getty Images.

Healthcare workers at Harborview Medical Center kept their scrub bottoms clean by wearing colorful patterned socks. Photo Courtesy of Karen Ducey for Getty Images.

To our dedicated healthcare heroes on the front lines, we thank you for your commitment to improving the health of the public.

Community support

Since the start of the pandemic, UW Medicine has experienced an outpouring of support from the community in the form of generous financial contributions and donations of PPE, meals, notes of appreciation and more.

"You guys are heroes," - @lizzo

— UW Medicine (@UWMedicine) March 31, 2020

💜💛 #WeGotThisSeattle pic.twitter.com/uupQC5z2kX

Learn how you can support our COVID-19 response and front-line workers at AccelerateMed.org/Heroes.

UW Medicine received generous donations from the community throughout this pandemic.

Sources

nytimes.com/2020/01/10/world/asia/china-virus-wuhan-death.html

newsroom.uw.edu/news/covid-19-coronavirus-spike-holds-infectivity-details

cdc.gov/media/releases/2020/s0229-COVID-19-first-death.html

cnbc.com/2020/03/11/who-declares-the-coronavirus-outbreak-a-global-pandemic.html

governor.wa.gov/news-media/inslee-extends-school-closures-rest-2019-20-school-year

newsroom.uw.edu/news/elective-procedures-delayed-support-covid-19-response

cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/cloth-face-cover-guidance.html

newsroom.uw.edu/news/philanthropists-respond-covid-19-care-research-needs

ipd.uw.edu/2020/04/with-an-emergency-meeting-rosettacommons-aims-to-accelerate-covid-19-research/

newsroom.uw.edu/news/blood-test-detects-past-infections-new-coronavirus

newsroom.uw.edu/news/remdesivir-speeds-recovery-cases-severe-covid-19

sciencedaily.com/releases/2020/05/200518144940.htm

newsroom.uw.edu/news/united-world-antiviral-research-network-uwarn-forms

who.int/news-room/detail/29-06-2020-covidtimeline

coronavirus.jhu.edu/data/state-timeline/new-confirmed-cases/washington